Limits of Interpreting A Drug Test

Showing: opiates

There are many variables regarding the analyses of substance abuse testing. Clients will often ask about specifics pertaining to the determination of time, dose and frequency when detecting substance(s) of abuse.

When testing a reservoir matrix- a material or substance which can accumulate and retain drug and alcohol biomarkers (eg., urine, blood, hair, nail, umbilical cord, or meconium, etc.), the reported quantitation of a drug or its metabolite cannot be used to determine when/if a specific substance was used, how much of a substance was used or how often a substance was used. Test results show only if a substance was detected or not detected.

A specimen’s window of detection provides an estimated timeframe for detecting substance(s) of abuse. Based on extensive research studies, the generally accepted windows of detection for specimens used in our testing are as follows:

- Scalp Hair- Up to approximately 3 months prior to collection.

- Fingernail- Up to approximately 3-6 months prior to collection.

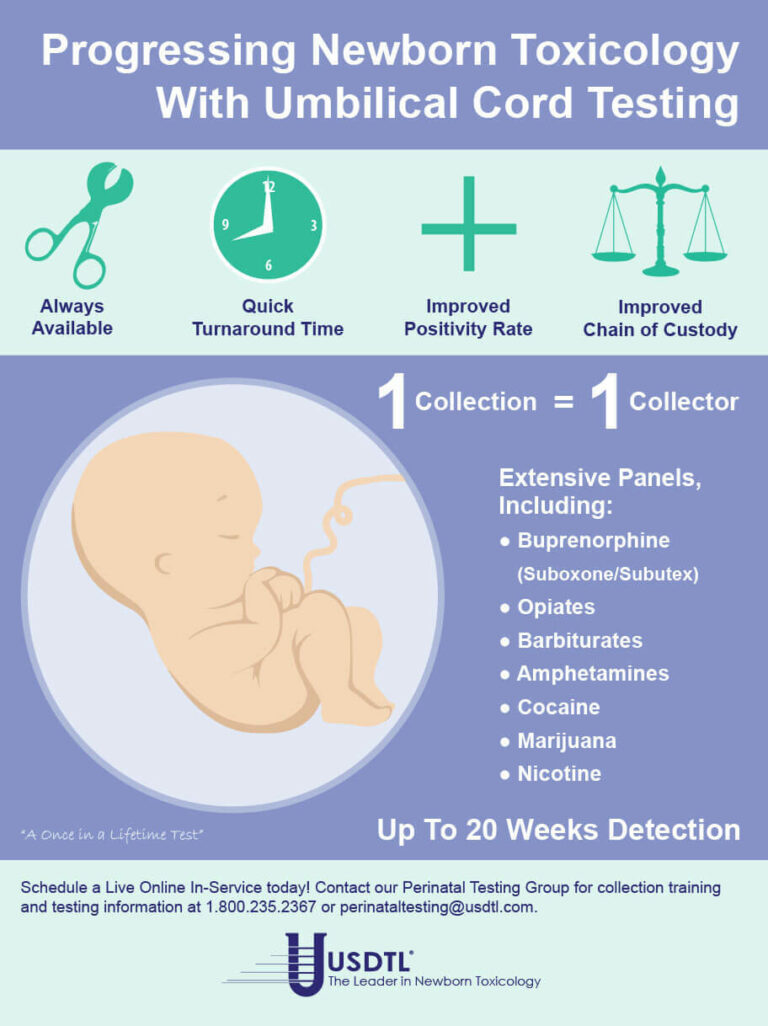

- Umbilical Cord- Up to approximately 20 weeks prior to birth.

- Meconium- Up to approximately 20 weeks prior to birth.

- Urine- Up to approximately 2-3 days prior to collection.

- Blood (PEth)-May be up to approximately 2-4 weeks prior to collection.

It is important to know that the interpretation of drug testing results may be determined by a Medical Review Officer (MRO). A Medical Review Officer is a licensed physician (MD or DO) who has knowledge of substance abuse disorders and has the appropriate medical training to interpret and evaluate an individual’s positive test result together with his or her medical history and any other relevant biomedical information.1This is an incredibly important aspect of drug testing. A laboratory can detect substances, but an MRO may be used to interpret what that detection means.

1. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine: (January 2003-Volume 45-Issue 1-p 102-103) Qualifications of Medical Review Officers (MRO’s) in Regulated and Nonregulated Drug Testing. Departments: ACOEM Consensus Opinion Statement

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal

By Freepik© Studio

Maternal Nonnarcotic Drugs that cause neonatal psychomotor behavior consistent with withdrawal.

The Onset of Newborn Withdrawal Symptoms is Highly Variable

| Drug | Onset of Signs |

| Diazepam | Hours to Weeks |

| Alcohol | 3-12 Hours |

| Heroin | 24 Hours |

| Sedatives | 1-3 Days |

| Methadone | 1-7 Days |

| Opiates | 1-7 Days |

| Barbiturates | 1-14 Days |

– Click here to download the pdf.

Read an excerpt from the article Neonatal Drug Withdrawal below:

Signs characteristic of neonatal withdrawal have been attributed to intrauterine exposure to a variety of drugs. Other drugs cause signs in neonates because of acute toxicity. Chronic in utero exposure to a drug (eg, alcohol) can lead to permanent phenotypical and/or neurodevelopmental-behavioral abnormalities consistent with drug effect. Signs and symptoms of withdrawal worsen as drug levels decrease, whereas signs and symptoms of acute toxicity abate with drug elimination. Clinically important neonatal withdrawal most commonly results from intrauterine opioid exposure. The constellation of clinical findings associated with opioid withdrawal has been termed the neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Among neonates exposed to opioids in utero, withdrawal signs will develop in 55% to 94%.1,2 Neonatal withdrawal signs have also been described in infants exposed antenatally to benzodiazepines,3,4 barbiturates,5,6 and alcohol.7,8

— Neonatal Drug Withdrawal https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212

References:

-

Harper RG, Solish GI, Purow HM, Sang E, Panepinto WC. The effect of a methadone treatment program upon pregnant heroin addicts and their newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1974 ; 54 (3): 300–305 [PubMed]

-

Ostrea EM, Chavez CJ, Strauss ME. A study of factors that influence the severity of neonatal narcotic withdrawal. J Pediatr. 1976; 88 (4 pt 1): 642–645 [PubMed]

-

Rementería JL, Bhatt K. Withdrawal symptoms in neonates from intrauterine exposure to diazepam. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (1): 123–126 [PubMed]

-

Athinarayanan P, Piero SH, Nigam SK, Glass L. Chloriazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976; 124 (2): 212–213 [PubMed]

-

Bleyer WA, Marshall RE. Barbiturate withdrawal syndrome in a passively addicted infant. JAMA. 1972; 221 (2): 185–186 [PubMed]

- Desmond MM, Schwanecke RP, Wilson GS, Yasunaga S, Burgdorff I. Maternal barbiturate utilization and neonatal withdrawal symptomatology. J Pediatr. 1972; 80 (2): 190–197 [PubMed]

- Pierog S, Chandavasu O, Wexler I. Withdrawal symptoms in infants with the fetal alcohol syndrome. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (4): 630–633 [PubMed]

- Nichols MM. Acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a newborn. Am J Dis Child. 1967; 113 (6): 714–715 [PubMed]

- The Detection of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, Delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol, Delta-10-tetrahydrocannabinol, and Cannabidiol in Hair Specimens

- Umbilical Cord Tissue Testing for Ketamine

- Drugs of Abuse: A DEA Resource Guide (2024)

- Beyond THC and CBD: Understanding New Cannabinoids

- New Xylazine, Psilocin, Gabapentin, Dextromethorphan, and Extended Cannabinoids Testing at USDTL

- Psilocin: The Magic Behind the Mushroom

- Fetal Fentanyl Syndrome: Why Detecting Newborn Fentanyl Exposure Matters Now More Than Ever

- DMT: An Overview

- October 2025 (1)

- July 2025 (3)

- May 2025 (2)

- April 2025 (2)

- March 2025 (2)

- February 2025 (1)