Blog

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal

By Freepik© Studio

Maternal Nonnarcotic Drugs that cause neonatal psychomotor behavior consistent with withdrawal.

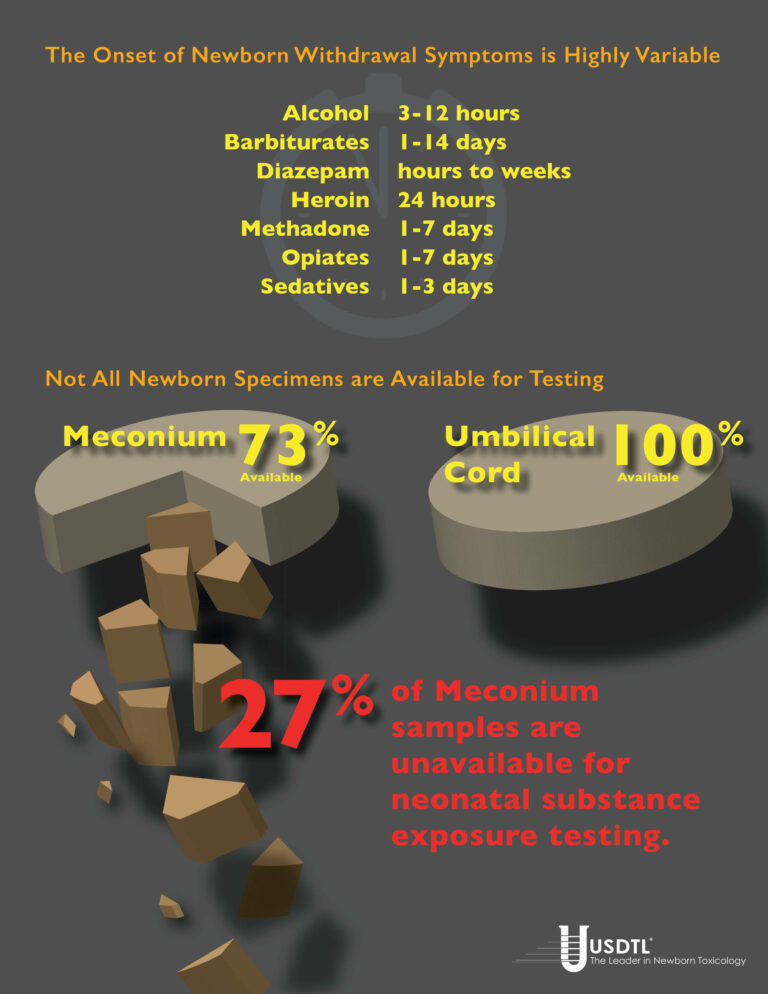

The Onset of Newborn Withdrawal Symptoms is Highly Variable

| Drug | Onset of Signs |

| Diazepam | Hours to Weeks |

| Alcohol | 3-12 Hours |

| Heroin | 24 Hours |

| Sedatives | 1-3 Days |

| Methadone | 1-7 Days |

| Opiates | 1-7 Days |

| Barbiturates | 1-14 Days |

– Click here to download the pdf.

Read an excerpt from the article Neonatal Drug Withdrawal below:

Signs characteristic of neonatal withdrawal have been attributed to intrauterine exposure to a variety of drugs. Other drugs cause signs in neonates because of acute toxicity. Chronic in utero exposure to a drug (eg, alcohol) can lead to permanent phenotypical and/or neurodevelopmental-behavioral abnormalities consistent with drug effect. Signs and symptoms of withdrawal worsen as drug levels decrease, whereas signs and symptoms of acute toxicity abate with drug elimination. Clinically important neonatal withdrawal most commonly results from intrauterine opioid exposure. The constellation of clinical findings associated with opioid withdrawal has been termed the neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Among neonates exposed to opioids in utero, withdrawal signs will develop in 55% to 94%.1,2 Neonatal withdrawal signs have also been described in infants exposed antenatally to benzodiazepines,3,4 barbiturates,5,6 and alcohol.7,8

— Neonatal Drug Withdrawal https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212

References:

-

Harper RG, Solish GI, Purow HM, Sang E, Panepinto WC. The effect of a methadone treatment program upon pregnant heroin addicts and their newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1974 ; 54 (3): 300–305 [PubMed]

-

Ostrea EM, Chavez CJ, Strauss ME. A study of factors that influence the severity of neonatal narcotic withdrawal. J Pediatr. 1976; 88 (4 pt 1): 642–645 [PubMed]

-

Rementería JL, Bhatt K. Withdrawal symptoms in neonates from intrauterine exposure to diazepam. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (1): 123–126 [PubMed]

-

Athinarayanan P, Piero SH, Nigam SK, Glass L. Chloriazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976; 124 (2): 212–213 [PubMed]

-

Bleyer WA, Marshall RE. Barbiturate withdrawal syndrome in a passively addicted infant. JAMA. 1972; 221 (2): 185–186 [PubMed]

- Desmond MM, Schwanecke RP, Wilson GS, Yasunaga S, Burgdorff I. Maternal barbiturate utilization and neonatal withdrawal symptomatology. J Pediatr. 1972; 80 (2): 190–197 [PubMed]

- Pierog S, Chandavasu O, Wexler I. Withdrawal symptoms in infants with the fetal alcohol syndrome. J Pediatr. 1977; 90 (4): 630–633 [PubMed]

- Nichols MM. Acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a newborn. Am J Dis Child. 1967; 113 (6): 714–715 [PubMed]

What You Need To Know: Testing for Drug Exposure vs. Ingestion

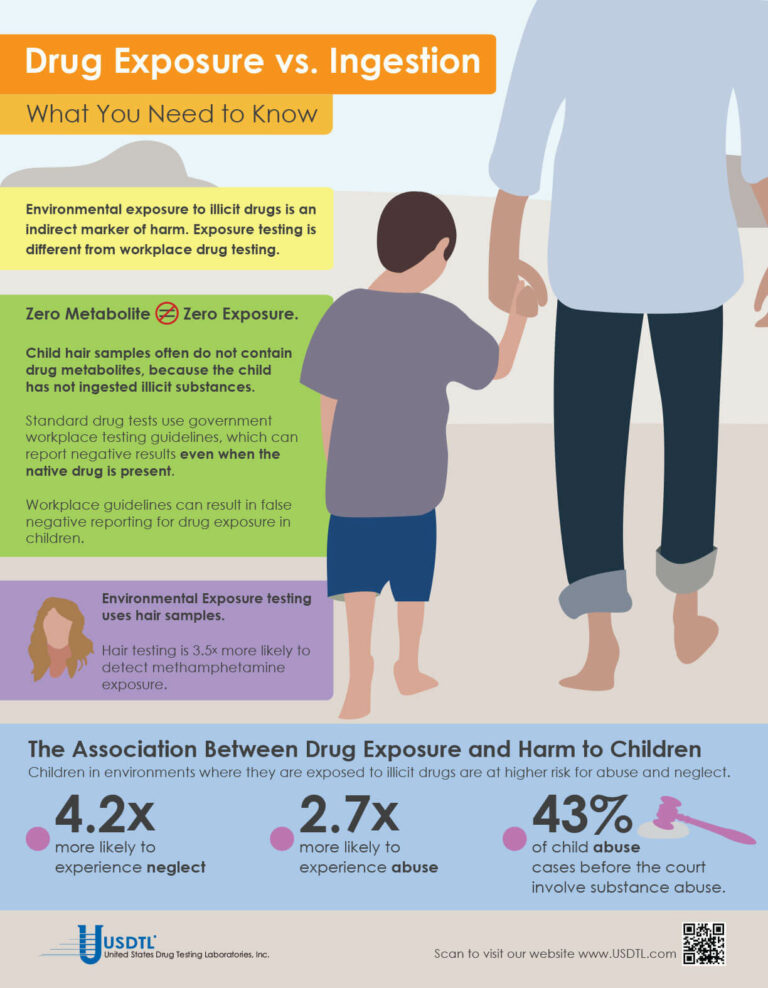

Testing for environmental exposure to illicit drugs is a powerful tool for protecting the welfare of children. Exposure testing is different from typical drug testing, and when properly done, has the potential to reduce the risk of harm to children.

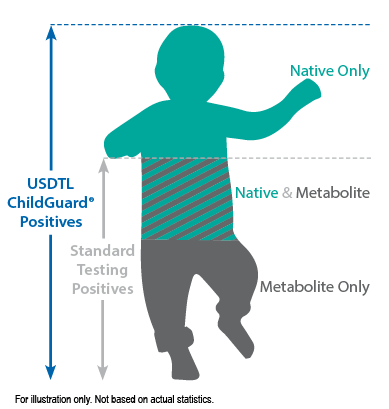

No Metabolite Does NOT Mean No Exposure

Testing labs often apply government workplace testing guidelines to child exposure testing samples. Under workplace guidelines, negative results are reported when drug metabolites are absent in the testing sample, even if the native drug is present.

Child hair and nail samples for exposure testing often do not contain drug metabolites because the child has not ingested illicit substances. Adhering to workplace guidelines can result in false negative reporting for drug exposure, especially when children are involved.

Environmental Exposure

Environmental Exposure testing is most effective in alternative sample types, such as hair and fingernails. For example, hair testing is 3.5x more likely to detect methamphetamine exposure than urine testing. Typical drug testing samples are washed to remove drug biomarkers resulting from exposure. Environmental exposure testing eliminates this step.

– Click here to download the pdf.

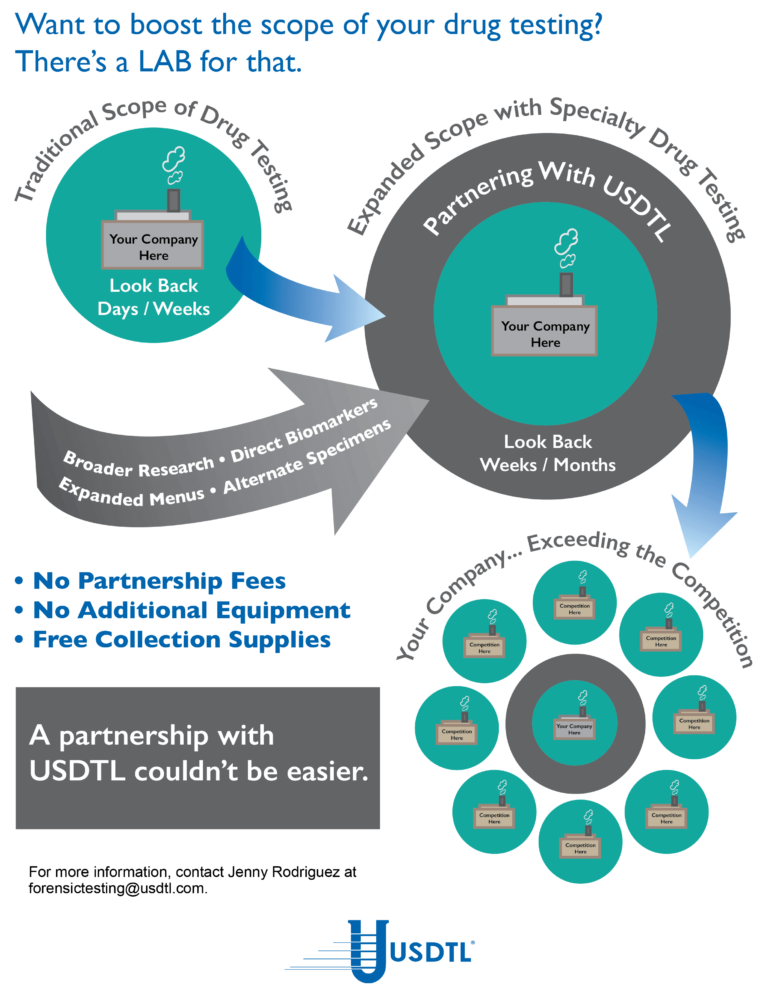

Numerous studies have shown that meconium specimens are too often unavailable for substance exposure testing. Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens offers a solution.

By Joseph Salerno

Unable, despite her best efforts to shake her addiction, a woman exposes her unborn child to drugs in the womb. The baby is born, healthy and beautiful with all the promise the future holds. Three days later, the withdrawal symptoms kick in. The baby wails, flush with the pains of withdrawal and inconsolable, unable to sleep, experiencing seizures. The NICU physician wants to know what the baby has been exposed to, but now it’s too late. The meconium has already been passed and discarded, and the umbilical cord is gone, lost opportunities for concrete answers. Now it’s a guessing game.

This isn’t just a “what-if” scenario, unfortunately, but a potential reality in a surprisingly large number of newborn substance exposure cases. Withdrawal symptoms in substance exposed newborns can be delayed up to three, five, even seven days after the baby is born. Cases of in utero barbiturate exposure may not manifest withdrawal signs until 14 days post-delivery. By that time it’s too late to test any of the baby’s specimens for biomarkers of substance exposure, because the specimens are gone.

Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens offers a solution to avoid this dilemma. Umbilical cord is the only universally available specimen for substance exposure testing. Numerous studies have shown meconium is not available for testing in up to 27% of births. Meconium may be passed in utero. In some cases, there is not enough meconium volume to test even when it is able to be collected.

And again, meconium may have been passed by the newborn and discarded well before they begin to exhibit withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, this can also be a problem when the signs of in utero substance exposure emerge after the umbilical cord has been discarded. Newborn urine testing is not a viable option in these cases, because urine provides only a 1-3 day window of detection for substance exposure biomarkers, compared to the 20 week look-back of umbilical cord.

Universal collection of umbilical cord specimens for every birth ensures there are no lost opportunities should the need for substance exposure testing arise. Umbilical cord collection is extremely easy, requiring very little additional effort during post delivery procedures. Only six inches of the cord is required for substance testing, taking up very little storage space.

Umbilical cord tissue is a very stable and reliable specimen. Cord tissue is stable up to 1 week at room temperature, and up to 3 weeks when refrigerated, without jeopardizing the testing results. This is ample time for the emergence of newborn withdrawal symptoms, even in the most extreme cases. Enough time to avoid a missed opportunity for real answers. Only one donor and one collector are present during the umbilical cord collection – in contrast to the multiple collections and multiple collectors involved with meconium – greatly improving chain-of-custody integrity. Umbilical cord specimens are ready for transport just minutes after the birth, greatly improving turnaround time for results reporting. Meconium passages can be delayed for days before being sent to the lab.

References

1. Arendt, R., Singer, L., Minnes, S. and Salvator, A. (1999). Accuracy in detecting prenatal drug exposure. Journal of Drug Issues. 29(2), 203-214.

2. Ostrea, E., Knapp, D., Tannenbaum, L., Ostrea, A., Romero, A., Salari, V. and Ager, J. (2001). Estimates of illicit drug use during pregnancy by maternal interview, hair analysis, and meconium analysis. Pediatrics. 138, 344-348.

3. Lester, B., ElSohly, M., Wright, L., Smeriglio, V., Verter, J., Bauer, C., Shankaran, S., Bada, H., Walls, C., Huestis, M., Finnegan, L. and Maza, P. (2001). The maternal lifestyle study: Drug use by meconium toxicology and maternal self-report. Pediatrics. 107(2), 309-317.

4. Derauf, C., Katz, A. and Easa, D.. (2003). Agreement between Maternal Self-reported Ethanol Intake and Tobacco Use During Pregnancy and Meconium Assays for Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters and Cotinine. American Journal of Epidemiology. 158, 705–709.

5. Eylera, F., Behnkea, M., Wobiea, K., Garvanb, C. and Tebb, I. (2005). Relative ability of biologic specimens and interviews to detect prenatal cocaine use. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 27, 677 – 687.

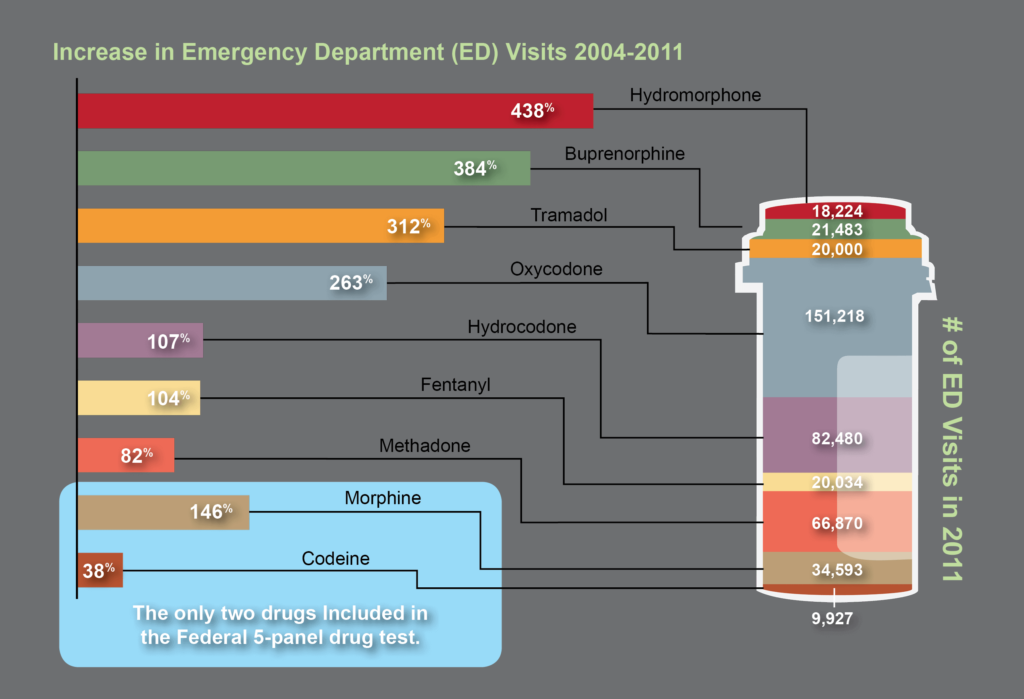

The need for opiate and drug testing has grown in the last three decades. 2.4 million people in the United States abused opioid pain relievers in 1985, the year before President Ronald Reagan announced his Federal Drug-Free Workplace Program.1 That number swelled to 4.9 million – a 104% increase – by 2012.2 During that same time, the population of the United States grew only 32%.

The original opiate testing panel created in 1986 is an incomplete tool for today’s drug testing needs. No other category of drugs has evolved as much as opiates and opioids. Addiction to high strength pain relievers and newer opioid compounds has eclipsed codeine, morphine, and heroin addiction addressed by the original 1986 five-panel drug test.

Based on the most recent data on emergency department visits related to illicit substance abuse, it is clear that opiate and opioid abuse has shifted dramatically. Screening for opiate abuse using only 1986 drug testing guidelines for the opiate drug class misses the past 30 years of pharmaceutical and drug testing advancements.3

References:

When a child is exposed to illegal substance abuse they often also face other coexisting obstacles to a normal life – neglect, abuse, violence, and other vulnerabilities. Substance abuse is a disease, one that often prevents adults from doing what is in a child’s best interests. Our environmental exposure test for children can help.

Our hair environmental exposure test is the only drug test designed to detect passive exposure to drugs and detect both native drugs and drug metabolites in the hair specimen. Drug metabolites are produced in the body only if drugs have been ingested. Children in drug exposed environments are most often not drug users themselves, so drug metabolites are typically absent in child specimens. However, the hair, like a sponge, can absorb non-metabolized drug (native drug) if it is exposed through things such as touching or being in contact with drugs or drug users.

Standard hair tests with other labs will only report a positive exposure result if drug metabolites are detected, even when the native drug is in the child’s hair specimen. Our hair environmental exposure test reports a positive result if either native drugs or drug metabolites are detected.

A hair exposure test can provide evidence of drugs in a child’s environment for the past 3 months. A positive test result suggests that the child has experienced one or more of the following: passive inhalation of drug smoke, contact with drug smoke, contact with sweat or sebum (skin oil) of a drug user, contact with the actual drug, or accidental or intentional ingestion of illegal drugs.

ChildGuard®is the only child hair test designed to detect exposure to native drugs and drug metabolites.

By Joseph Salerno

The movement and location of physical evidence from the time it is obtained until the time it is presented in court is the legal definition of chain of custody. The results of any newborn alcohol or substance of abuse test performed at USDTL may eventually be presented as evidence in a court of law, and this is why USDTL maintains universal chain of custody regardless of the client source of testing specimens. A court can exclude the results of a test if a chain of custody for the newborn sample was not maintained by the hospital and USDTL.

Chain of custody for specimens sent to USDTL is maintained as a chronological paper trail of collection and transfers of specimens throughout the testing process. The paper trail is signed and dated by each person who handles the specimen, both when they receive the specimen into their own hands, and when they hand it off to the next person in the process. Less transfers of a specimen that need to be documented is better for the chain of custody overall. A well maintained and legal chain of custody begins at the time of specimen collection and continues uninterrupted until test results have been presented in court, if necessary.

There are several key elements of the chain of custody for alcohol and drug test samples that must be present when samples arrive at USDTL. First, the specimen container must be sealed with an intact security seal. Next, the sample must be accompanied by a Chain of Custody and Control Form with an identification number matching the number on the specimen container. The Chain of Custody and Control Form is the first piece of the chain of custody paper trail. Thirdly, the Chain of Custody and Control Form must be signed and dated by an authorized agent from the client. If one or more of these elements are missing, USDTL must return the sample to the client.

An unbroken chain of custody ensures sample integrity in several ways that preserve the legal usefulness of alcohol and drug testing results.

Chain of custody ensures that the original sample is the same as the one that is tested and ensures that the integrity of the sample is preserved during transport. Tampering, substitution, or alteration of the sample prior to being tested is prevented by the chain of custody process, which ensures thatit has been handled only by the donor, a qualified collector, and lab testing personnel.

Maintaining chain of custody for newborn samples destined for alcohol and drug testing is a simple process, but all those who handle a drug testing specimen need to be vigilant about the process nonetheless. Diligent maintenance of chain of custody is always in the child’s best interest. Unfortunately, it is only when the legal impact of an improperly maintained chain of custody is realized, that the full value of a well maintained chain of custody is understood. Ultimately, chain of custody protects the institution that is collecting the specimen, as well as the newborn whose health and well-being may rely on the results of a USDTL alcohol or drug test.

Reference: Giannelli, P. (1996). Forensic Science: Chain of Custody. Criminal Law Bulletin, 32(5), 447-465.

Please click here to read the full article by Eric Frazer, Ph. D., and Linda Smith, Ph. D., in our Fall issue of Substance.

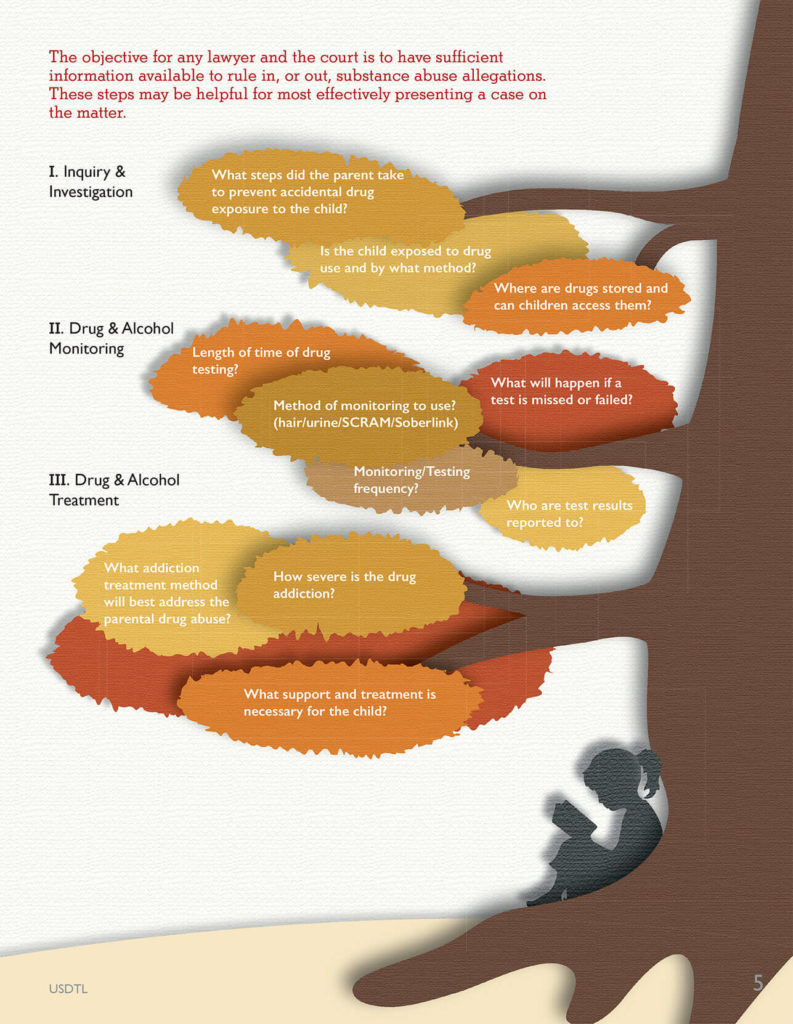

One of the most common issues that arises in Juvenile and Family Court is parental substance abuse. Once this allegation has been raised, there is immediate concern about the child’s safety and well-being. In particular, there is often concern about neglect and abuse. For example, will the parent prioritize drug seeking over caring for the child? Will the parent drive under the influence, with the child in the vehicle? Less commonly mentioned in the courtroom, especially in the family courtroom, is potential child exposure to drugs. Unfortunately, this is a significant risk to children, and should be considered and discussed in every case.

One of the challenges family lawyers and courts face is how to properly investigate the substance abuse allegation and determine if it is a valid concern. Gathering and organizing the most relevant information has historically been difficult to do because of a lack of awareness regarding what is most relevant and important. Fortunately, the drug testing lab can bridge that gap of uncertainty, especially when there is an allegation about child exposure.

The objective for any lawyer and the court is to have sufficient information available to rule in, or out, the substance abuse allegations. This information may be presented via admissible evidence, witness testimony, and/or expert testimony. The following pointers may be helpful to legal professionals so that they are able to most effectively present a case on this matter.

Step 1 – Inquiry & Investigation

One of the first steps in evaluating a substance abuse allegation is to ask research informed questions so that the most relevant data can be gathered. Questions should be focused on potential exposure of the children to parental drug possession or use. For example, relevant questions may include:

- Where does the defendant allegedly store the drugs?

- Does the child have easy access to these storage containers and locations?

- Is the child typically present when the drugs are used?

- In what ways may the child have been exposed?

- What steps, if any, did the parent take to protect the child from accidental exposure?

Step 2 – Drug & Alcohol Monitoring

If a parent tests positive on an alcohol or drug test, this may result in a motion, agreement, or court order for ongoing monitoring. However, many questions then arise. For example, how long should the monitoring extend? Should it

include both alcohol and drugs? What type of drug monitoring method should be used (urine/hair/SCRAM/Soberlink, etc.)?

- Drug Classes and Neurotransmitters: Amphetamine, Cocaine, and Hallucinogens

- Environmental Exposure Testing for Delta-8 THC, Delta-9 THC, Delta-10 THC, and CBD

- Bromazolam and Synthetic Benzodiazepines

- Winter Weather Delay Update

- Tianeptine

- Revolutionizing DUI Interventions: Wisconsin’s Breakthrough in Biomarker Testing for Impaired Drivers

- 3 FAQs You Should Know About Newborn Drug Testing

- The Brain Chemistry Behind Tolerance and Withdrawal

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (3)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (1)